|

The End

of AT&T

Ma Bell

may be gone, but its innovations are everywhere

By Michael Riordan

It's 1974. Platform shoes

are the height of urban fashion. Disco is just getting into full stride. The

Watergate scandal has paralyzed the U.S. government. The new Porsche 911 Turbo

helps car lovers at the Paris motor show briefly forget the recent Arab oil

embargo. And the American Telephone & Telegraph Co. is far and away the largest

corporation in the world.

AT&T's US $26 billion in

revenues—the equivalent of $82 billion today—represents 1.4 percent of the U.S.

gross domestic product. The next-largest enterprise, sprawling General Motors

Corp., is a third its size, dwarfed by AT&T's $75 billion in assets, more than

100 million customers, and nearly a million employees.

AT&T was a corporate

Goliath that seemed as immutable as Gibraltar. And yet now, only 30 years later,

the colossus is no more.

Of the many events that

contributed to the company's long decline, a crucial one took place in the

autumn of that year. On 20 November 1974, the U.S. Department of Justice filed

the antitrust suit that would end a decade later with the breakup of AT&T and

its network, the Bell System, into seven regional carriers, the Baby Bells. AT&T

retained its long-distance service, along with Bell Telephone Laboratories Inc.,

its legendary research arm, and the Western Electric Co., its manufacturing

subsidiary. From that point on, the company had plenty of ups and downs. It

started new businesses, spun off divisions, and acquired and sold companies. But

in the end it succumbed. Now AT&T is gone.

The company—still a

telecom giant but more focused on the corporate market—agreed to be acquired by

one of the Baby Bells, SBC Communications Inc. of San Antonio, in a deal valued

at $16 billion. In a few months, AT&T's famous ticker symbol—T, for

telephone—will disappear from the New York Stock Exchange listings, and the

company that grew out of Alexander Graham Bell's original telephone patents will

officially cease to exist.

Should we mourn the loss?

The easy answer is no. Telephone providers abound nowadays. AT&T's services

continue to exist and could be easily replaced if they didn't.

But that easy answer

ignores AT&T's unparalleled history of research and innovation. During the

company's heyday, from 1925 to the mid-1980s, Bell Labs brought us inventions

and discoveries that changed the way we live and broadened our understanding of

the universe. How many companies can make such a claim?

The oft-repeated list of

Bell Labs innovations features many of the milestone developments of the 20th

century, including the transistor, the laser, the solar cell, fiber optics, and

satellite communications. Few doubt that AT&T's R&D machine was among the

greatest ever. But few realize that its innovations, paradoxically, contributed

to the downfall of its parent. And now, through a series of events during the

past three decades, this remarkable R&D engine has run out of steam.

WHEN THE AT&T

MONOPOLY HELD SWAY over U.S. telecommunications, R&D managers at Bell

Labs and Western Electric were assured steady funding that allowed them to look

forward 10 or 20 years—the kind of long view that truly disruptive technologies

need in order to germinate and thrive. That combination of stable funding and

long-term thinking produced core contributions to a wide variety of fields,

including wireless and optical communications, information and control theory,

microelectronics, computer software, systems engineering, audio recording, and

digital imaging. Accumulating more than 30 000 patents, Bell Labs also played

host to a long string of scientific breakthroughs, garnering six Nobel Prizes in

physics and many other awards.

The funding came in large

part from what was essentially a built-in "R&D tax" on telephone service. Every

time we picked up the phone to place a long-distance call half a century ago, a

few pennies of every dollar—a dollar worth far more than it is today—went to

Bell Labs and Western Electric, much of it for long-term R&D on

telecommunications improvements.

In 1974, for example, Bell

Labs spent over $500 million on nonmilitary R&D, or about 2 percent of AT&T's

gross revenues. Western Electric spent even more on its internal engineering and

development operations. Thus, more than 4 cents of every dollar received by AT&T

that year went to R&D at Bell Labs and Western Electric.

And it was worth every

penny. This was mission-oriented R&D in an industrial context, with an eye

toward practical applications and their eventual impact on the bottom line.

AT&T's commitment to R&D

stemmed mainly from its pre-World War I experiences in developing high-power

vacuum tubes for use as amplifiers for transcontinental telephone service.

Facing scrappy competition from a hornet's nest of local phone companies after

Bell's original patents had expired, AT&T saw its leadership threatened—even

though it controlled about half the country's telephones.

The company wanted to

expand and offer "universal service" to its customers, aiming to put its phones

in every home and office across the country and connect them with one another.

But that required a very-low-distortion amplifier, or repeater, that could allow

AT&T to provide something no other company was offering: coast-to-coast

telephone calls.

In 1912, Harold D. Arnold,

a young Ph.D. physicist fresh from the University of Chicago, joined AT&T's

engineering department. He began trying to improve the performance of the

low-power Audion triode tube invented by Lee de Forest several years earlier.

Arnold coated the tube's tungsten cathode with an oxide layer to encourage the

emission of electrons and pumped out excess air molecules from the tube that he

figured were impeding current flow through it. The resulting high-power vacuum

tubes performed splendidly, regenerating voice signals sent over long distances

with minimal distortion.

Using repeaters based on

Arnold's tubes, AT&T created a sensation in 1915 at the Panama-Pacific

International Exposition in San Francisco, where the company demonstrated

transcontinental service for the first time. From AT&T headquarters in New York

City, Alexander Graham Bell once again uttered his famous command into the

mouthpiece, "Mr. Watson, come here. I want you." From San Francisco, his old

assistant bellowed back, "It will take me five days to get there now!"

For the next half century,

AT&T had the U.S. transcontinental telephone market all to itself—an advantage

that helped the company reestablish its monopoly, bringing many of the small

local phone companies under the umbrella of its Bell System. Thus, firmly

convinced of the value of investing in research and development, in 1925, AT&T

managers reorganized most of the company's R&D activities into a single

organization: Bell Telephone Laboratories.

The first Bell Labs

headquarters, in a gracious, sun-filled, 12-story building at 463 West St. in

New York City, looking out across the Hudson River, soon became home to 2000

scientists and engineers. Its founding president, Frank B. Jewett, would later

help lead the United States' R&D efforts during World War II, as president of

the National Academy of Sciences from 1939 to 1947.

AS AN INDUSTRIAL

LABORATORY, Bell Labs was primarily committed to improving AT&T's

telephone operations. But Jewett and Arnold, his first director of research,

wisely supported projects whose results might not necessarily be useful in the

short run. Their commitment to such basic research was quickly rewarded in 1927

by a scientific breakthrough of epic proportions.

Observing electrons as

they sped through a vacuum tube and ricocheted from a nickel crystal, physicist

Clinton J. Davisson recognized that beams of these feisty subatomic particles

seemed to behave like waves! The intriguing hypothesis that matter could have

wavelike properties, proposed by Louis de Broglie, was just then the subject of

heated debate in Europe. Davisson's serendipitous discovery of electron waves

went a long way toward verifying de Broglie's theory—and earned him half of the

1937 Nobel Prize in physics, the first for Bell Labs.

The quantum description of

matter that emerged from that 1920s' ferment soon found practical applications

in the work of other Bell Labs scientists. It became essential to understanding

electrical conduction in semiconductors such as silicon and germanium that

emerged from the World War II U.S. radar program, in which Bell Labs and Western

Electric played key R&D roles. This emerging quantum theory of solids was also

crucial to the postwar invention of the transistor by physicists John Bardeen,

Walter H. Brattain, and William B. Shockley—then working at Bell Labs' new home,

a sprawling suburban campus in Murray Hill, N.J.

But the transistor was

still a long way from becoming the mass-produced gizmo that would reshape—or

create—huge industries, including radio, television, microelectronics, and

aerospace. More than a decade of development—involving silicon purification,

crystal growing, and the diffusion of chemical agents called dopants into

semiconductors—was required before transistors could begin to assume the forms

they are found in today. Much of that work took place not at Bell Labs but at

two Western Electric plants in Pennsylvania, in Allentown and nearby Reading,

where engineers developed the precision manufacturing processes and techniques

needed to mass-produce transistors. The clean room, used today in almost every

aspect of semiconductor manufacturing, was born and raised in Allentown.

"Bell Laboratories

scientists in Murray Hill, N.J., may have won the Nobel Prizes and gotten most

of the press, but Allentown and Reading delivered the goods," notes Stuart W.

Leslie, a historian of science at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. "Their

research and production engineers, tool-and-die makers, layout operators, and

assembly-line workers figured out how to transform prize-winning research into

devices that were reliable, durable, consistent, and cheap."

Many other innovations

spewed forth from Bell Labs during the 1950s in the wake of the transistor's

invention, for which Bardeen, Brattain, and Shockley received the 1956 Nobel

Prize in physics. Silicon technology spawned the integrated circuit. It also led

to the solar cell, which provided a durable power source for generations of

satellites in succeeding decades. And electrical engineer John R. Pierce

perfected the wartime traveling-wave radar tube into an efficient microwave

source to make his dream of satellite communications a reality. He played a key

role in the development of Telstar, the satellite that carried an amplification

circuit designed to retransmit signals over enormous distances.

Then, in 1964, using a

huge horn-shaped antenna salvaged from the Telstar project, physicists Arno A.

Penzias and Robert W. Wilson accidentally stumbled across the dim afterglow of

the universe's birth: the remnant microwaves from the big bang. Their discovery

triggered a revolution in cosmology and earned them a 1978 trip along the by

then well-worn path from Bell Labs to Stockholm.

BUT AT&T'S

MAGNIFICENT R&D PROGRAM, which helped the company consolidate its

monopoly and dramatically improve phone service for its customers, also

contributed to the company's dissolution, as noted by Christopher Rhoads in a

recent Wall Street Journal article. Consider, for example, the transistor, the

invention that today lies at the heart of all things digital, from DVD players

to satellite transponders. AT&T at first licensed the patent rights to the

invention for a paltry $25 000 and later put them in the public domain as part

of a 1956 consent decree that averted a court breakup of the monopoly.

AT&T leaders recognized

that the transistor was just too important to keep to themselves—and the courts

probably would not have allowed that anyway. But more than that, Bell Labs and

Western Electric actively encouraged the diffusion of their semiconductor

technology by offering a series of workshops during the 1950s that were well

attended by engineers from many other companies. The participants included Jack

Kilby, who would go on to pioneer the integrated circuit at Texas Instruments,

and a handful of engineers from a small Tokyo electronics firm that would parlay

early success with the transistor radio into a decades-long dominance of

consumer electronics: Sony. If the invention of the transistor can be said to

have sparked the information age, it really became a global phenomenon after

those workshops helped stoke the fires.

At the time, Bell Labs

managers generally regarded their company as a quasi-public institution

contributing to the national welfare by enriching the country's science and

technology. Seen in that light, AT&T's vigorous promotion of semiconductor

technology made good sense—especially during a time the company was churning out

profits and didn't feel any competition breathing down its neck.

But such generosity may

have been one of the crucial forces behind its eventual downfall, as smaller,

nimbler, and more legally unfettered firms seized the opportunity to develop and

deploy innovations that would help undermine AT&T's dominance of U.S.

telecommunications. "After its forced breakup in 1984," The Wall Street

Journal's Rhoads wrote, "it was slowly crushed by technologies that drove down

the price of a long-distance call, and more recently by wireless calling and

Internet phoning."

At the same time Bell Labs

and Western Electric were working on their many innovations, there was a

resistance to rapid change rooted deep within the parent company's culture.

According to Sheldon Hochheiser, former AT&T corporate historian, "a service

ethos and the absence of the countervailing pressures of competition produced a

corporate culture dominated to a great degree by an engineering mentality." That

culture, he adds, "encouraged a value system where managers tended to take the

time to get innovations right, as an engineer would define right."

Thus, AT&T engineers

usually emphasized reliability and robustness of the network over the rapid

introduction of advanced technologies. Often a decade or more passed before new

features, such as long-distance direct dialing and touch-tone phones, would

finally percolate throughout the system. And cellular telephony, first described

in detail by Bell Labs engineers in 1947, never gained widespread commercial

operation as part of the Bell System.

PERHAPS THE MOST

EGREGIOUS EXAMPLE of the company's technological conservatism was the

languid introduction of electronic switching, conceived in the 1930s by Bell

Labs research director Mervin J. Kelly (who later became president). Kelly was

the one who had hired Shockley, directing him to find a solid-state replacement

for the electromechanical relays used in the switches in the Bell System's many

central offices.

The noisy, clunky relays

opened and closed circuits to establish continuous physical connections between

any two phones. A solid-state switch, on the other hand, would have no moving

parts, making it smaller, faster, quieter, and more reliable. Although

electronic switches based on solid-state components had been developed by 1959,

AT&T didn't introduce the first digital switch into the Bell System until 1976.

And electronic switching was still being gradually rolled out well into the

1980s, when AT&T's monopoly on telephone service came to an abrupt end. The much

more rapid introduction of digital switches by MCI and Sprint probably

contributed to AT&T's downfall.

And even though Bell Labs

and Western Electric developed most of the underlying silicon technology

required for the integrated circuit, which eventually became the guts of the

electronic central-office switch, AT&T wasn't in on its creation. The upstarts

Fairchild Semiconductor and Texas Instruments, focused as they were on

miniaturizing electronics for their military and aerospace customers, led the

way instead. Here again, AT&T engineers probably contributed to the lapse by

insisting on high-performance discrete components built for 40-year lifetimes in

the Bell System. There was no great drive for miniaturization in the system,

acknowledged Ian Ross, the president of Bell Labs at the time of the breakup.

"The weight of the central offices was not a big concern," Ross said.

Another factor

contributing to the technological inertia was the billions of dollars already

sunk into the Bell System. Any responsible corporate manager would prefer to

amortize such investments before introducing newer, better devices, especially

when no real competitors existed. As the historian Hochheiser notes, the

"absence of competition allowed the Bell System's managers the freedom to take

an extremely long view."

THAT ABILITY TO

TAKE THE LONG VIEW was a boon to Bell Labs researchers, who could

follow their own instincts and explore what especially intrigued them, rather

than what might bolster AT&T's bottom line during the next few years. "The only

pressure at Bell Labs was to do work that was good enough to be published or

patented," recalls Morris Tanenbaum, who developed the first silicon transistor

in 1954 [see "The Lost History of the Transistor," IEEE Spectrum, May 2004] and

rose to the upper echelons of Bell Labs management in the 1970s.

With ample offices and

well-equipped lab space, lush green surroundings, classy cafeterias, and an

extensive library, the Bell Labs campus in Murray Hill became a magnet for some

of the best scientists and engineers in the world. Given broad research freedom,

they rewarded their far-sighted employer with a remarkable series of

technological firsts, right up to and beyond the 1984 breakup of AT&T.

Take researchers Izuo

Hayashi and Morton Panish, for example. In 1970 they developed the first

semiconductor lasers able to function at room temperature—a prerequisite for use

in CD and DVD players, printers, bar-code scanners, and fiber-optic networks. At

about the same time, Willard Boyle and George Smith invented the charge-coupled

device, or CCD, which is now the heart and soul of digital imaging, with

millions produced annually for digital cameras. Meanwhile, Bell Labs researchers

created the Unix operating system and the C programming language and its

offshoots [see sidebar,—key computer-engineering developments that helped other

companies such as Sun Microsystems flourish.

And the world-class

science continued well into the 1980s. Arriving at Bell Labs in 1978, physicist

Steven Chu got to spend six months figuring out what excited him the most and

was told to settle for nothing less than "starting a new field." He says he felt

he was among the elect, "with no obligation to do anything except the research

we loved best." Chu rewarded his employer's confidence with the development of a

laser method to cool atoms. That research, which earned him a share of the 1997

Nobel Prize in physics, is now allowing others to explore the quantum behavior

of atoms and molecules.

Over the past two decades,

however, basic and applied research have increasingly parted company at AT&T.

Many of Bell Labs' best scientists have left since the 1984 breakup. Then came

the 1996 spin-off of Lucent Technologies Inc., which inherited most of Bell

Labs. The exodus of top talent continued and accelerated after the collapse of

Lucent's stock in the past few years and a highly publicized scandal over

fabrication of data by physicist Jan Hendrik Schön. The departing scientists

have joined the legions of Bell Labs alumni already in academic

positions—including Chu, who just replaced another AT&T alumnus, Charles Shank,

as the director of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California.

The Bell Labs budget has

suffered, too, as R&D funding at Lucent has plummeted in the past few years. In

2003, with R&D expenditures of $1.49 billion (down from $2.31 billion in 2002),

it was outspent by 56 companies around the world. Having recently returned to

profitability in large part by cutting back on research, Lucent will be lucky to

remain in the top 100.

IN RETROSPECT, IT

SEEMS UNREASONABLE to expect that a publicly held corporation can

devote so much money to long-term research when facing the ruthless forces of

the marketplace. AT&T added tremendous value to society, but as a condition of

its regulated monopoly status, the company was not allowed to commercialize new

technology that was not directly related to telephony.

Nor could AT&T charge

customers for the technology except through its fees for telephone equipment and

services. When it was a regulated monopoly, the company could build into those

charges a pittance devoted to risky future-oriented research, such as setting up

a solid-state physics department in the postwar years. But as ordinary

corporations competing for customer dollars after the breakup and later

spin-off, AT&T and Lucent could afford no such luxury.

We the customers are the

ultimate losers. A vigorous, forward-looking society needs mechanisms like this

to set aside funds for its long-term technological future. Letting governments

serve the purpose is an imperfect alternative at best, fraught with the

difficulty of making wise choices. The peer-review process widely used to select

projects may be able to direct public funds to worthwhile research, but it

usually favors established scientists and often overlooks bright young

researchers—such as Chu—with bold but risky ideas.

AT&T, Bell Labs, and

Western Electric effectively diverted a tiny fraction of our everyday

expenses—and from all corners of the U.S. economy—into long-term R&D projects in

an industrial setting that could, and often did, make major improvements in our

lives. Today we are eating up the technological capital they built during those

amazingly productive years. Are we doing anything to replace it?

ABOUT

THE AUTHOR

MICHAEL RIORDAN teaches the history of physics and technology

at Stanford University and the University of California, Santa Cruz.

TO

PROBE FURTHER

A detailed

account of the transistor's invention and development can be found in

Crystal Fire: The

Birth of the Information Age, by Michael Riordan and Lillian Hoddeson

(W.W. Norton & Co., 1997).

The major events that led

to AT&T's demise are discussed in The Fall of the Bell System: A Study in

Prices and Politics, by Peter Temin with Louis Galambos (Cambridge

University Press, 1987).

A timeline with AT&T's

innovation milestones is available at

http://www.att.com/history.

The above article was

archived from

http://www.spectrum.ieee.org/WEBONLY/publicfeature/jul05/0705att.html

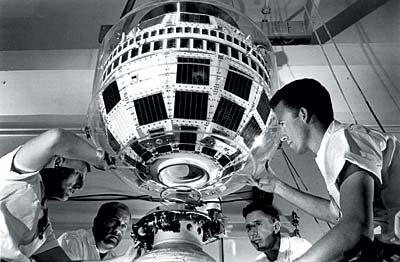

INNOVATION MACHINE: Technicians attach the 77-kilogram Telstar 1

satellite to a launching rocket for its journey into orbit in 1962.

A scientist

performs an acoustic experiment at Bell Labs' anechoic chamber, a room devoid of

echoes and reverberations.

Bell Labs

researchers in Murray Hill, N.J., invented the transistor, but a Western

Electric plant in Allentown, Pa., developed most of the precision manufacturing

processes needed to mass-produce it.

PHOTOS:

LUCENT TECHNOLOGIES/BELL LABS (3

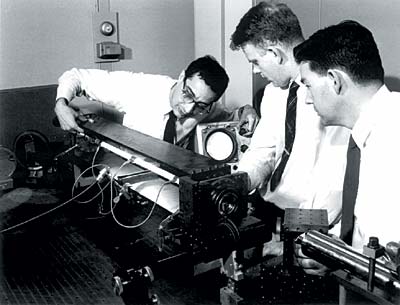

MAKING LIGHT WORK:

Ali Javan, William Bennett, and Donald Herriott [from left] adjust the

helium-neon laser they developed in 1960. The device, which generated a

continuous visible laser beam, found applications in science and industry.

BELL'S

NOBELS

In its 80 years, Bell Labs

has garnered six prizes in physics

1937—WAVE NATURE OF

MATTER

By firing an electron beam

at a nickel crystal, Clinton J. Davisson showed that the ricocheting electrons

diffracted just like electromagnetic waves. His demonstration of the electron's

wave nature eventually led to solid-state physics. George P. Thomson shared the

prize.

1956—THE TRANSISTOR

Put semiconductors

together the right way and you can make them amplify and switch signals. The

invention of the transistor by John Bardeen, Walter H. Brattain, and William B.

Shockley made all digital devices possible.

1977—ELECTRONS IN

IMPERFECT CRYSTALS

How do electrons behave

inside metal alloys and noncrystalline materials like glass? Philip W. Anderson

came up with a quantum mechanical model, work that earned him a Nobel prize,

shared with Nevill F. Mott and John H. van Vleck. It found practical

applications with the development of memory chips and other solid-state devices.

1978—COSMIC MICROWAVE

BACKGROUND

Probing the sky with a

radio antenna originally developed for satellite communications, Arno A. Penzias

and Robert W. Wilson detected a faint microwave echo of the universe's birth.

Their discovery provided key support for the big bang theory.

1997—LASER COOLING

By shining converging

laser beams at a group of atoms, Steven Chu was able to slow the atoms and

reduce their temperature almost to absolute zero. This "optical molasses" effect

led to atomic lasers and to improved atomic clocks and navigation devices. Chu

shared the prize with Claude Cohen-Tannoudji and William D. Phillips.

1998—THE FRACTIONAL

QUANTUM HALL EFFECT

Using a powerful magnetic

field, Horst L. Störmer, Robert B. Laughlin, and Daniel C. Tsui put electrons

into a quantum state with liquidlike properties. The phenomenon, called the

"fractional quantum Hall effect," is shedding light on the behavior of electrons

and other elementary particles.

A FAMOUS VISITOR:

Frank B. Jewett [right], soon to be Bell Labs' first president, shows high-power

vacuum tubes to Joseph J. Thomson, who discovered the electron.

NOT JUST

HARDWARE

Unix

was another Bell Labs brainchild

Today, Unix, in all of its

variants, descendants, and imitators, is easily the most influential operating

system in the world. MS-DOS, the foundation on which Windows was built, started

out as a poor man's Unix. Apple's Mac OS X, as well, comes from a version of

Unix created at the University of California, Berkeley. And, of course, Unix was

the model for Linux. But despite its importance, Unix's 1969 origin at Bell Labs

began with an outright failure, a system called Multics.

Today, Unix, in all of its

variants, descendants, and imitators, is easily the most influential operating

system in the world. MS-DOS, the foundation on which Windows was built, started

out as a poor man's Unix. Apple's Mac OS X, as well, comes from a version of

Unix created at the University of California, Berkeley. And, of course, Unix was

the model for Linux. But despite its importance, Unix's 1969 origin at Bell Labs

began with an outright failure, a system called Multics.

Back in the 1960s,

multimillion-dollar dinosaurs such as the IBM 360 bestrode the computing

landscape. Powerful as they were, mainframes were single-user machines until

time-sharing systems were developed. Multics was to be one of them. Developed

jointly by Bell Labs, GE, and MIT, the creators of Multics had an ambitious

goal. They were to design a system that would meet "almost all of the present

and near-future requirements of a large computer utility," according to a 1965

planning document.

Four years later, a

commercially viable system was still a distant goal. Bell Labs withdrew from the

project, but a core group of researchers there, led by Kenneth Thompson [seated

in photo above] and Dennis Ritchie [standing] continued their research on

operating systems. Thompson devised the file system that lies at the heart of

Unix. (He also wrote a game called Space Travel that spurred the development of

the operating system itself by showing what resources a program needed to be

able to run.)

By the late 1960s,

minicomputers were scurrying about the computer world, and the post-Multics

group was allowed to buy a Digital Equipment Corp. PDP-11 (a bargain at only US

$65 000). The first PDP-11 version of Unix was a wonder, a mere 16 kilobytes in

size, with 8 KB of memory for additional software. The first Unix application

would be a word-processing program to be used by AT&T's patent-writing group.

The experiment was a success; other AT&T divisions began using Unix, and the new

operating system was off and running. When AT&T published the code and made it

available for noncommercial use, UC Berkeley; Carnegie Mellon, in Pittsburgh;

and other schools created even richer systems. A generation of software

developers would grow up with Unix in one form or another.

Soon, Thompson decided to

write a Fortran compiler for the new operating system. What he came up with,

though, was a new programming language, similar to the Basic Combined

Programming Language, or BCPL, that had been written for Multics. He dubbed it

"B." By 1971 it had evolved to become the C language. Today, most major software

projects are written in C or its descendant, C++, which itself was invented at

Bell Labs, by Bjarne Stroustrup in the early 1980s.

—Steven

Cherry

PHOTO:

LUCENT TECHNOLOGIES/BELL LABS

We Offer Personalized One-On-One

Service!

Call Us Today at (651) 787-DIAL (3425)

"Breaking Up Is Hard

To Do!"

Events that led up to

the demise of the Bell System

"The Bell

System as we have known it will exist only in our

memories and in the history books." December 31, 1983

CONTENTS:

-

Introduction

-

Time Line - "Chronicle News Update"

-

Timeline of

the Legal History of

Telecommunications

and the Divestiture of AT&T

-

Restructuring Plan

(January 1983)

-"The Road Map to Divestiture"

-

"Plan of

Reorganization" - Legal Document - Civil Action No. 82-0192, December 16,

1982.

-

The Road Ahead - An excellent series of articles

published in the Bell Telephone Magazines at the time of divestiture

explaining how the FCC and DOJ rulings will affect the employees, the

customers and the resulting companies created by the breakup of Ma Bell.

-

Standing way back

from the legal nuts and bolts -

An outline

of a book conceived but never published by Dennis Sandow of Millington, NJ.

-

Obituaries

-

How the Bell System

Looks to the Public

by Louis

Harris, from the Bell Telephone Magazine, Autumn 1978 issue

-

WHITHER DIRECTORY AND VIDEOTEX OPERATIONS?

- Of the 10 modifications Judge Harold H. Greene mandated in the agreement

between AT&T and the Department of Justice, one that has called for a great

deal of corporate adjustment is the provision setting forth conditions under

which printed Yellow Pages, White Pages directories, and electronic

information services may be provided. To read the entire article, click

HERE.

-

Dear Reader: We Stopped the Presses

- The divestiture announcement just made it

into the Bell Telephone Magazine's last issue for 1981 which was to be printed

in January 1982.

Related

pages on this site:

INTRODUCTION

Before 1984, the United States public network

utilized practices, procedures, and equipment largely determined by AT&T and the

Bell System. The network performed exceedingly

well and, for customers, life was simple. With the advent of divestiture in

1984, when AT&T and its operating telephone companies parted company, the

Department of Justice's Modification of Final Judgment broke the seamless

national network into 164 separate pieces called Local Access and Transport

Areas (LATAs) to handle local phone traffic. Through this move the DOJ created

two distinct types of service providers local exchange carriers (LECs) and

interexchange carriers (IXCs).

The divestiture of AT&T (A.K.A. "Ma Bell")

was very costly both to AT&T, the Baby Bells and the consumer. Litigation

costs alone for AT&T up to the January 8, 1982 announcement of divestiture was

360 million dollars along with an additional 15 million dollars of costs to the

federal government. But the costs didn't stop there. To get an idea

of just how costly this was to both the former Bell System companies and the

consumer, see this excerpt

from the book "The Rape of Ma Bell."

A judge in Philadelphia by the name of

Harold H. Greene took up the case of whether the United States government had

legally granted the Bell system monopoly status. The judge decided that the Bell

system was illegal and therefore had to be broken up. But how, and what were to

be the new rules? The judge spent the rest of his professional life dealing with

the can of worms that he created. He would rule over how the Bell System would

look in the future, right down to who would got to paint their vans in the old

telephone colors and how a microwave tower in the middle of nowhere would be

divided to handle telephone traffic. Yet this man knew nothing of

telephone business or how it functioned!

As noted on my

Bell System History page from a 1983

sign that hung in many Bell System facilities, "There are two giant entities

at work in our country, and they both have an amazing influence on our daily

lives . . . one has given us radar, sonar, stereo,

teletype, the transistor, hearing aids, artificial larynxes, talking movies, and

the telephone. The other has given us the Civil

War, the Spanish American War, the First World War, the Second World War, the

Korean War, the Vietnam War, double-digit inflation, double digit unemployment,

the Great Depression, the gasoline crisis, and the Watergate fiasco.

Guess which one is now trying to tell the other one how to run its business?"

Once Judge Greene made the judgment that

he was the all-knowing supreme being of the Supreme Court, people looked to him

for all kinds of decisions. The process was extremely expensive for the

consumer, filled the lawyers pockets with money, gave us rates five times

higher, and eventually bankrupt companies such as WorldCom (owner of MCI.)

It has been a rocky road for AT&T since

divestiture. Many post-divestiture business plans failed miserably such as

the attempt to enter the computer manufacturing business and the purchase of

NCR. Tens of thousands of employees lost their jobs after the demise of

the Bell System. An AT&T document that shows a timeline of events for the

ten years that followed the divestiture can be viewed by clicking

HERE.

An official announcement to the Bell

System employees shortly after the January 8, 1982 ruling by the U.S. Department

of Justice (referred to below as the DOJ) took place in the form of a video

taped show called "Chronicle News Update - A Historical Decision. Some

highlights of that tape are provided here.

Key dates in

the eventual demise of the Bell System:

-

November

20, 1974 - DOJ files antitrust suit charging anticompetitive

behavior, and seeking breakup of Bell System.

-

February

4, 1975 - AT&T formally denies all charges.

-

June 21, 1978 - Case

reassigned to Judge Harold Greene.

-

September 11, 1978 -

Judge Greene lays down new schedule for discovery and trial preparation.

-

November 1, 1978 - DOJ

files its first statement of contentions and proof, settling out detailed

charges.

-

September 9, 1980 - Judge

Greene schedules beginning of trial for January 15, 1981.

-

January 15, 1981 - Trial

begins with opening arguments.

-

January 16, 1981 - Judge

Greene grants parties' request for recess until February 2, 1981 to work on

a "concrete, detailed proposal for settlement.

-

January 30, 1981 - Judge

Greene extends recess through March 2, 1981.

-

February 23, 1981 - DOJ

advises court it will not be able to approve a final agreement by deadline;

settlement talks break off.

-

March 4, 1981 - Trial

resumes; testimony begins.

-

March 23, 1981 - Defense

Secretary Caspar Weinberger.

-

July 1, 1981 - DOJ rests

its case.

-

July 10, 1981 - AT&T

files motion for dismissal.

-

July 29, 1981 - DOJ

requests 11 month delay to permit Congress to consider amendments to S.898.

-

August 3, 1981 - AT&T

begins its defense.

-

August 6, 1981 - DOJ says

it will pursue case while Administration seeks passage of amended S.898.

-

August 10, 1981 - DOJ

says it would drop case if acceptable legislation enacted.

-

August 17, 1981 - DOJ

files reply to AT&T dismissal motion, saying it will pursue case.

-

September 11, 1981 -

Judge Greene rules on dismissal, dropping some charges, but permitting bulk

of case to go forward.

-

October 26, 1981 - Court

sets schedule that will end AT&T testimony by January 20, 1982. Judge

Greene indicates a verdict could be handed down by end of July, 1982.

-

December 31, 1981 - DOJ

announces that parties have resumed discussions to try to bring the case to

a resolution.

-

January 8, 1982 -

Antitrust suit dropped after AT&T accepts government's proposal.

-

January 1, 1984 - Bell

System no longer exists

Here are some

screen shots of the newscast outlining the key points of post divestiture of the

Bell System:

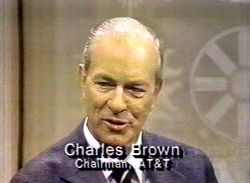

Below are more

screen shots from video tape showing (left to right) the Chronicle News

anchorpersons, Chairman of AT&T, and the Vice President of AT&T at the

time of the divestiture announcement. As with above images, click on the

images below to see full-size screen capture of video frame.

Click

HERE

to see how CNN news announced the breakup.

Timeline of

the Legal History of

Telecommunications

and the Divestiture of AT&T

1876 - Alexander Graham Bell receives a basic patent on his "talking

machine."

1885 -The American Telephone and Telegraph Company was established as a

subsidiary of the American Bell Telephone Company to operate the long distance

connections among the rapidly growing local Bell telephone companies.

1900 - AT&T was reorganized into a holding company, becoming the

parent of the Bell companies, and making Western Electric the exclusive

manufacturing arm of the Bell System.

1907 - Following the expiration of Bell's original patents, the industry

entered a period of unrestrained competition, and as a result, by 1907,

independent telephone companies had almost as many phones in service as the Bell

System (about 3,000,000 each).

1913 - After a series of acquisition wars in which AT&T emerged

victorious, in 1910, the Interstate Commerce Commission began the first

investigation of AT&T's monopoly activities. As a result, in 1913, AT&T

promised the government to allow independent phone companies to interconnect

with its toll facilities, and to refrain from acquiring any more competing

independent companies. This established the cooperative, non-competing

relationship between the Bell System and the approximately 1,500 independent

telephone companies, which largely exists today, and consolidated AT&T's

monopoly power.

1934 - AT&T owns four out of every five telephones in the country,

its long distance network ties together the country's telephone system and

nearly every major city is served by a Bell telephone company. The

Communications Act of 1934 is passed by Congress, establishing the Federal

Communications Commission, which governs the telephone and broadcast

industries.

1956 - The government and AT&T signed a consent decree, which

enjoined AT&T only from engaging in any business other than provision of

common carrier communications services -- it was thus excluded from the computer

industry in the United States -- and barred Western Electric from any activity

other than manufacturing equipment of a type to be used to provide telephone

service. AT&T was also required to license Bell patents to any applicant in

exchange for royalties.

1959 - The seeds of competition in the long distance market were sown

when several large business users of long distance, dissatisfied with the price

and quality of AT&T services, applied to the FCC for permission to build

their own private microwave systems. In the Above 890 decision, the Commission

found that an adequate number of microwave frequencies were available to serve

both common carrier (AT&T was using these frequencies only to transmit

television signals) and private networks. The Above 890 decision not only caused

AT&T to hasten its development of more efficient microwave systems, but

created the first long distance price competition when AT&T, in response,

filed its first tariffs for bulk line discounts. Almost ten years later, after

numerous AT&T procedural delays, the FCC found that the "Telpak"

discount rate tariff was illegal because it was priced well below AT&T's

costs.

1963

- Microwave Communications, Inc. (later re-named MCI) requests permission from

the FCC to build a microwave system between St. Louis and Chicago, arguing that

it could provide better and cheaper private line service between customer

locations in these cities. The Commission approved the application, but not

until 1969.

1969 - The FCC, by a 4-3 vote, grants MCI's application to establish a

limited private line microwave long distance system between St. Louis and

Chicago, asserting that such service was in the public interest. This decision

marked the beginning of a competitive market in long distance services.

1971 - In its Specialized Common Carrier decision, the FCC firmly

establishes a national policy of open entry into private line and specialized

common carrier markets. The decision also changed previous pricing practices,

allowing for the first time a variety of services at a variety of prices

tailored to various needs. The FCC issues a decision in its First Computer

Inquiry, drawing a line between data processing (computer-based) services and

communications services, which were to continue being regulated, in order to

avoid the possibility of underwriting profit-making competitive activities with

revenues from regulated telephone company activities. Because of the 1956

consent decree, AT&T was barred from offering data processing services even

through a separate subsidiary. In 1973, in a case brought by GTE, the

Commission's authority to draw such a line was upheld.

1972 - MCI begins commercial operation of private line service between

St. Louis and Chicago.

1973 - The FCC permits "value-added networks" (VANS) into the

communications market. These carriers lease private lines from other telephone

companies, and with the addition of computer enhancements, sell those lines for

the express purpose of transmitting data and information service.

1974 - The

Department of Justice files a new, and much more comprehensive, antitrust suit,

which charged AT&T with illegal actions designed to perpetuate its monopoly in

telephone service and equipment. The suit asks for the divestiture of Western

Electric and "some or all of the Bell Operating Companies." For the next several

years, the parties argued jurisdictional issues and undertook a lengthy

discovery process, delaying the start of the trial until 1981.

From Bell Telephone Magazine -

Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"[1984 was] A trying year for the Bell

System. In March, MCI files suit against AT&T in U.S. District Court in Chicago,

charging AT&T with "monopolizing the business and data communications market."

Bristling at the charge, AT&T files a countersuit, charging MCI with attempting

to restrain trade and lessen competition by obstructing or harassing other

common carriers. The controversy prompts the FCC in April to begin a broad

inquiry into the economic impact of competition, particularly the effect of

interconnection and the use of customer-provided equipment. Thanksgiving Week,

AT&T learns it is again being sued, this time by the federal government. The

Department of Justice files suit against AT&T November 20, charging that the

company has unlawfully monopolized the telecommunications markets. It alleges,

among other things, that AT&T has attempted to restrict and eliminate

competition from other common carriers, private telecommunications systems, and

other manufacturers and suppliers of telecommunications equipment, and that AT&T

requires the operating companies to purchase Western Electric products. The case

is assigned to Joseph E. Waddy, a federal district court judge in Washington, D.

C."

1975 -

From Bell Telephone Magazine - Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"AT&T contends that the suit is without

merit and insists that it has broken no antitrust laws. AT&T and Justice lawyers

devote the rest of the year to drawing up rules for "discovery," the process by

which each party examines the other's key documents and witnesses. AT&T begins

to build a staff to provide documents to Justice. Ironically, as AT&T prepares

to meet charges that it monopolizes the telecommunications business, the FCC in

November accelerates competition by authorizing direct connection to the network

of customer-provided equipment registered with the FCC.

AT&T introduces "One Bell System. It

works." as the central theme for a long-range information program on the value

of the integrated Bell System structure. The need for a more widespread

understanding of the Bell System as a whole is at the heart of the information

program."

1976 - In its Resale and Shared Use decision, the FCC allows unlimited resale and shared use of private line services and facilities. (Resellers lease bulk rate lines from telephone companies and resell them at a discount.) However, in ordering telephone companies to sell lines for resale, the Commission determined that, when they offer interstate communications, resellers are common carriers and must be regulated. With its efforts to maintain its monopoly losing at the FCC and in the courts, AT&T turns to Congress. The Consumer Communications Reform Act, the first comprehensive attempt to modify the Communications Act since it was enacted in 1934, is introduced. This bill became known as the "Bell Bill". Intensive lobbying by AT&T produces more than 200 co-sponsors for the Bell Bill, which would have restored AT&T's monopoly and stripped the FCC of its regulatory authority over competitive entry in long distance. The legislation was bottled up for months in both Houses of Congress, which explored telephone industry competition issues for the first time in a series of well-publicized hearings.

From Bell Telephone Magazine - Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"A watershed year for AT&T and

the telecommunications business on three fronts -- regulation, legislation, and

litigation.

Regulation: The FCC clears a

number of long-standing dockets. Among other things, it rules that AT&T is

entitled to a higher interstate rate of return and approves the expansion of the

Dataphone® Digital Service.

The deadline for registering

telephone equipment for connection to the network is set, postponed, then

modified, with staggered deadlines for registering ancillary, data, and basic

voice telephone equipment.

In another major decision, the

FCC -- completing two years of study -- concludes in its economic impact inquiry

that competition has not had, and is not likely to have, significant adverse

impact on telephone company revenues

or rates for basic exchange service. Commissioner Benjamin Hooks dissents, and

AT&T says it is in "virtually total disagreement" with the FCC's conclusion.

One of the most significant

FCC inquiries begins in August. Recognizing that technological advances and

changing customer needs have blurred the distinctions between data processing

and communications, the FCC decides to re-examine the rules it set in its 1971

Computer Inquiry. The object of this second inquiry -- called Computer Inquiry

II (CI-2) -- is, among other things, to find ways to allow common carriers to

benefit from new data processing technology. In November, the FCC overrules its

Common Carrier Bureau and allows the Bell System to sell the Dataspeed ® 40/4

terminal, which the bureau argued was data processing equipment.

Legislation: The introduction

of the Consumer Communications Reform Act (CCRA) in the House and Senate

launches a six-year national debate on national telecommunications policy. The

measure is promptly labeled "the Bell bill" by detractors. By the time the 94th

Congress adjourns, however, there are 192 sponsors of one or another of five

versions of CCRA -- 175 in the House and 17 in the Senate.

Litigation: Nearly three years

after the filing of the case, Judge Waddy, on October 20, rules that the Justice

Department's antitrust suit is proper and that he has jurisdiction. AT&T appeals

the decision."

1977 - The U.S. Court of Appeals issues its Execunet decision, which opened the long distance market to full competition by reversing FCC decisions limiting MCI and other specialized carriers to private line services. In subsequent decisions (Execunet II, 1978 and Execunet III, 1981) the court ruled that AT&T and its local telephone companies must permit the other long distance carriers to interconnect to their local networks to start and complete their calls.

From Bell Telephone Magazine - Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"Nearly a year after AT&T's appeal, the

Supreme Court declines to review the decision of Judge Waddy, whose poor health

is now noticeably slowing the case's progress. The FCC's request for comments in

CI-2 draws responses from 50 parties, including AT&T and other carriers, the

Justice Department, IBM, data processing equipment and services companies,

industry associations, and users. Most want data processing to remain free from

regulation. AT&T suggests new rules be adopted to allow it and other carriers to

provide a full range of innovative communications services.

A new CCRA is introduced in the House

on the opening day of the 95th Congress. A Senate version is introduced soon

after. Hearings by the House and Senate are held throughout the year. Proposals

are made by two industry task forces -- including one on separating

telecommunications businesses into competitive and non-competitive sectors."

1978 -

From Bell Telephone Magazine - Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"AT&T chairman John D. deButts calls it

a "year to be proud of," citing the beginning of a national switched data

network, a vigorous international sales effort, and the second restructuring of

the Bell System in five years. The company begins changing from a

services-oriented to a market-oriented organization, separating the residence

and business operations into major profit centers.

New congressional voices are heard in

the continuing debate over national telecommunications policy.

Representatives Lionel Van Deerlin

(D.-California) and Louis Frey (R.-Florida) introduce the Communications Act of

1978, a rewrite rather than a revision of the Communications Act of 1934.

Hearings are held across the

country, but Van Deerlin's bill is still in committee at year's end.

The antitrust case is assigned in June

to Judge Harold H. Greene because Judge Waddy is seriously ill. Although nearing

its fifth year, the case has yet to go to trial. Greene, a 13-year veteran of

the bench, is reported determined

to treat the suit "just like any other case, because the parties and the public

have a right to expect a federal judge to move things along." Three months

later, he issues a pre-trial order that puts lawyers for both sides on a strict

schedule designed to get the trial under way by Fall, 1980. To speed up the

process, he gives AT&T and Justice deadlines for filing statements detailing

what they intend to prove and what witnesses and evidence they'll use to do so.

AT&T and Justice lawyers begin the

process of "stipulation," during which each side sorts out the facts they can

agree on, leaving only the remainder to be decided in court."

1979 - After the Execunet decision, AT&T files a tariff at the FCC to raise the cost of specialized carriers' interconnection with AT&T's local network by 300%. Those carriers had vastly inferior connections into AT&T's local network (creating poor connections and necessitating dialing multidigit access numbers). They charged that AT&T was attempting to make it too expensive to compete in the long distance market.

From Bell Telephone Magazine - Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"In a 'tentative decision' released in

July, the FCC says it will 'adopt a flexible regulatory scheme' in CI-2. In

brief, the FCC says it will allow common carriers to set up separate

subsidiaries to sell detariffed enhanced 'nonvoice' services. AT&T endorses the

concept but is concerned about specifics.

AT&T vice chairman James E. Olson

cautiously notes that 'controversy seems to be giving way to consensus' on

telecommunications legislation, helped in large part by President Carter's call

for action. By the end of the year, after another series of House and Senate

hearings, a new House bill is introduced, sponsored by 15 members of the

telecommunications subcommittee. The bill, H.R. 6121, deals strictly with common

carrier issues, no longer touching on the broadcast or CATV industry as other

bills

did.

1980 - The FCC issues a second Computer II decision that completely deregulated all data processing services. The decision also totally deregulated customer premises equipment and removed it from the rate base. Further, the decision allowed AT&T and GTE (the country's second largest telephone company) to sell customer premises equipment, but only through a separated subsidiary with separate accounting systems. The FCC allows the resale of public switched network services like MTS (regular long distance service) and WATS,

establishing a market that today accounts for a growing share of competitive

long distance service.

From Bell Telephone Magazine - Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"April 7, four years after it began

CI-2, the FCC announces one of the most momentous decisions in its history --

the detariffing of all new customer premises equipment and of all enhanced

communications services.

AT&T and GTE are required to set up

separate subsidiaries. The decision is made public in a 31/2-hour meeting. The

FCC sets the detariffing date as March 1, 1982. (Later, the subsidiary

requirement will be modified to apply only to Bell, and the detariffing date

will be extended to January 1, 1983.)

The FCC's decision sparks legislative

efforts to forge new telecommunications policy, but both House and Senate bills

become snagged after preliminary approvals by the respective subcommittees.

The bills die at the end of the 96th

Congress. In the Senate, committee leaderships pass from the Democrats to the

Republicans; in the House, the failure of Representative Van Deerlin to be

re-elected means a change in

the influential telecommunications subcommittee.

Throughout the year, lawyers for

Justice and AT&T file outlines of their cases in preparation for trial.

Meanwhile, in June, the MCI antitrust suit filed against AT&T in 1974 comes to a

conclusion.

A jury awards MC1600 million dollars, a

figure automatically trebled to 1.8 billion dollars because antitrust violations

are involved. (AT&T is still awaiting a decision from the Seventh Circuit Court

on an appeal of that verdict.)"

1981

- On January 15, the U.S. v. AT&T antitrust trial begins, and is immediately recessed amid speculation that a settlement is imminent. However, negotiations between the Department of Justice and AT&T broke down and the trial resumed on March 4. At the conclusion of the government's case, AT&T moved to dismiss the suit, but U.S. District Judge Harold Greene, concluding that "the testimony and the documentary evidence adduced by the government demonstrate that the Bell System has violated the antitrust laws in a number of ways over a lengthy period of time," continued the trial. Late in the fall, H.R. 5158 is introduced in the House, once again promoting competition as a cornerstone of national communications policy by providing for separate subsidiaries for AT&T's competitive activities, and offering a system for deregulating communications markets when they became fully competitive.

From Bell Telephone Magazine - Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"Justice's antitrust suit finally

begins to move along. After years of developing evidence and filing pre-trial

briefs, lawyers for AT&T and Justice

say on January 5 that they have agreed on the "concept" of a settlement, the

first public hint of a possible conclusion to the long and trying case. When

Justice and AT&T can't agree on the details for settling the case, the first

witness is called. This is March 4, 61/2years after the suit began.

William F. Baxter, newly appointed as

assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department's antitrust

division, vows in his first press conference to litigate the case "to the

eyeballs," which quells rumors that Justice, under President Reagan, might seek

a compromise to end the case quickly. Baxter runs into opposition from the

Defense and the Commerce departments, however, and asks for an ll-month recess

to permit Congress to address the issue. Judge Greene refuses and Justice rests

its case.

Judge Greene also refuses AT&T's motion

to dismiss the case. Justice, he says, has shown "that the Bell System has

violated the antitrust laws in a number of ways over a lengthy period of time."

AT&T begins its defense, but

three months later, on New Year's Eve, Judge Greene is told the two parties have

begun negotiating out-of court. Despite the time the antitrust suit is

consuming, the Bell System continues planning and implementing organizational

changes to comply with the FCC's Computer Inquiry II decision.

On the legislative front, the Senate in

October passes S. 898, the Telecommunications Competition and Deregulation Act

of 1981, which AT&T chairman C.L. Brown calls "the most significant milestone

yet in the effort to forge legislation." The bill is sent to the House, where

Representative Timothy E. Wirth (D.- Colorado) introduces a new bill, H.R. 5158,

which is substantially different from S. 898."

1982

- On January 8, faced with the reality of having to finish the antitrust trial before a judge who had clear doubts of its innocence, and with the increasing prospect of legislation mandating competition in communications markets (but not divestiture), AT&T agrees to a

settlement of the antitrust suit proposed by the Justice Department. The settlement would require the breakup of the Bell System, the same relief the government had sought from the beginning of the antitrust case in 1974. Under the proposed settlement, AT&T retained its long distance services, Western Electric, and Bell Laboratories, and gave up its 22 local monopoly telephone companies. AT&T was barred from "electronic publishing" over its own lines, and a maximum amount of AT&T debt that could be assumed by each operating company was established. The settlement proposal required the local telephone companies -- by September 1986 -- to provide access to all long distance carriers "equal in type, quality and price" to that provided by AT&T, and prohibited the local companies from manufacturing telephone equipment. Publishing of the highly profitable Yellow Pages was to have been awarded to AT&T. The proposal, however, was subject to approval by Judge Greene after a period of public comments. After announcement of the divestiture agreement, H.R. 5158 is modified to allow the local telephone companies to market customer premises equipment and publish the Yellow Pages. Consideration of the legislation was ended in mid-July, while it was being debated in the full Energy and Commerce Committee, because of inordinate delays and dilatory tactics by AT&T's few supporters on the Committee. In August, after a nine-month review of the divestiture agreement, Judge Greene enters a

Modified Final Judgment (MFJ) in settlement of the antitrust case. While substantially accepting the terms agreed to by AT&T and the Department of Justice, Greene, in order to strengthen the financial viability of the local telephone companies, permits them to market customer premises telephone equipment and to publish the Yellow Pages. The FCC extends its Competitive Carrier deregulation of the interstate telephone industry, ruling that it will rely on market forces instead of regulation to control the rates of all carriers except AT&T, under a policy known as "forbearance." In December, the FCC announces the first of several decisions on access charges -- the prices charged to the competitive long distance carriers by local telephone companies for hooking into the local network -- in the post-divestiture environment. The access charge decision proposed a radical change in the way the fixed costs of the local telephone network were paid. The previous system had been designed so that the cost of equipment used by local and long distance carriers for long distance service -- wires, poles, switches, etc. -- would be shared by long distance and local service. The access charge order shifted almost all of those costs onto telephone subscribers, who pay a flat monthly fee whether or not they make any long distance calls. At the same time, three years before equal access for all long distance carriers, giving them the same connections as AT&T, was to be implemented, and with little improvement in the connections long distance carriers were getting from AT&T, the Commission orders a doubling of the ENFIA rate the other carriers were paying to AT&T and local Bell companies.

From Bell Telephone Magazine - Issue 3 & 4, 1982:

"Fateful Friday, as some financial

analysts tag January 8, is the 129th scheduled day of the trial. AT&T's Brown

and Justice's Baxter announce a resolution of the suit at a joint press

conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. AT&T agrees to divest

the 22 Bell operating companies, representing two-thirds of AT&T's assets and

accounting for a third of its 6.9 billion dollars in net 1981 income.

On the grounds that their 23-page

agreement is a modification of the 1956 Consent Decree, Justice and AT&T file

for approval in Federal District Court in Newark, New Jersey, which handled the

1956 Decree. The 1982 agreement is referred to as the Modification of Final

Judgment (MFJ).

Judge Vincent Biunno of the New Jersey

court approves the settlement, but Judge Greene refuses to close the 1974

antitrust suit, claiming he still holds jurisdiction. In a complicated series of

legal moves, Judge Greene is given complete authority to approve or reject the

agreement, and Judge Biunno's approval is "vacated."

Judge Greene contends that the

agreement deserves the full public scrutiny provided by the Tunney Act, which

governs antitrust settlement procedures. The public is given 60 days to comment

after Justice publishes a comprehensive description of the Decree in newspapers

across the country. The 60-day period for comment begins February 19; a second

round of comments is provided for and ends June 14.

Meanwhile, the announcement of an

agreement has stirred congressional waters. On March 22, Representative Wirth

introduces more restrictions on the Bell System in H.R. 5158, weeks after top

AT&T and Bell System officers strongly criticize the bill. The amended bill is

approved 15-0 by the House telecommunications subcommittee and sent to the full

House energy and commerce committee for consideration.

AT&T quickly responds. In an

unprecedented move, it urges share owners and employees to write and visit their

congressional representatives to oppose the bill, and runs full-page ads

denouncing the bill in newspapers across the country. Congressional offices are

reported swamped with anti-legislation mail. On July 20, Wirth withdraws H.R.

5158 for the rest of the year.

After months of reviewing the 4,000

pages of public comments, briefs, and the responses of the parties in the case,

Judge Greene on August 11 issues a 178-page opinion on the Modification of Final

Judgment. He characterizes it as "plainly in the public interest" but wants 10

changes. He wants, among other things, to allow the operating companies to

provide new customer premises equipment and printed Yellow Pages and to prohibit

the remaining AT&T from offering electronic publishing services over its own

transmission facilities for at least seven years.

Eight days later, AT&T and Justice, in

separate actions, notify the judge that they will accept his recommendations.

Justice is uncomfortable with the change that allows the divested companies to

provide new customer premises equipment, but says it will agree to the Order

even if the judge doesn't change his mind. Judge Greene doesn't. On August 24,

two hours after he receives a revised MFJ signed by AT&T and the Department of

Justice, Judge Greene approves the agreement.

In the 2,834 days since the suit was

filed, AT&T has spent more than 380 million dollars and employed more than two

thousand people to meet the demands of the court and the Justice Department and

to prepare its defense. The approval of the MFJ is the culmination of years of

debate on national telecommunications policy. It sparks the beginning of the

most massive structural change in any company in the nation's history."

1983 - Throughout the year, many of the local telephone companies petition state regulatory commissions for massive, unjustified rate increases. While publicly implying that they were needed because of the costs associated with divestiture, the companies' filings indicated no such reasons. In the pre-divestiture confusion, many of those requests were granted, and implemented after the divestiture in 1984. In response to these extraordinary requests for local rate increases, by the soon-to-be-divested Bell Operating Companies, in November the House passes H.R. 4102, which prohibited the FCC from imposing access charges on residential subscribers and continued the discount for specialized carriers' access.

1984 -Bowing to pressure from the House and a highly critical letter from 35 members of the Senate, the FCC agrees to reconsider its access charge decision, and, at the same time, rescinds the proposed increase in ENFIA rates. On January 1, the divestiture went into effect, with AT&T providing long-distance services and equipment manufacture and sales, and seven regional holding companies, comprising local telephone companies with separate, "unregulated" subsidiaries for competitive activities, providing local telephone service. In July, equal access is introduced for the first time in Charlestown, West Virginia, by the newly divested Bell Atlantic Corporation. This permits telephone subscribers to call MCI and other non-AT&T long-distance companies by dialing "1+". On September 1, each of the seven Regional Companies begins offering equal access in a small number of locations under the terms of "Appendix B" of the

MFJ.

Click on cartoon above to view full-size.

(Contributed to this web site by Diane)

The following is an

article from the Southern Bell Magazine dated January, 1983. It gives some

historical insight into how the divestiture was to happen:

Restructuring Plan (as of

January 1983)

The Road Map to Divestiture

Last month another major phase in the largest corporate

restructuring in American history was completed.

AT&T submitted to the Federal District Court in

Washington, D.C., and the Department of Justice its

comprehensive plan for

the reorganization of the Bell System.

The 471-page filing details how the company proposes to

divest, as of Jan. 1, 1984, the assets, work force and stock ownership of

the Bell System's 22 operating companies in compliance with the consent

decree agreed to by AT&T and the Department of Justice and approved by the

court on Aug. 24, 1982.

Because dividing Bell System assets is a major portion of

the work needed to implement restructuring, AT&T also submitted a "Bell

System Asset Assignment Detail Work Plan." The Work Plan sets forth

instructions, including inventory forms, that will be used to carry out the

separation of all operating company facilities and books of accounts. These

procedures are being field-tested by the operating companies to make

preliminary assignments. However these assignments are subject to any

modifications in the proposed Local Access and Transport Area (LATA)

boundaries or the reorganization plan.

Under the terms of the decree, the operating companies

will provide exchange and local access service and may provide printed

directory advertising and new customer premises equipment.

AT&T will provide interexchange long distance telephone

service and other products and services. AT&T will also assume

responsibility for embedded customer premises equipment (CPE) , which is

equipment on customers' premises or in operating company inventory. By the

time divestiture occurs, AT&T will already be in the new CPE and enhanced

services businesses through its subsidiary, American Bell Inc., as required

by the Federal Communications Commission's Second Computer Inquiry order.

The Bell System reorganization plan must be approved by

the court. The plan is also subject to review and comment by state

regulators, consumer groups, competitors and other interested parties.

Final court action is expected this spring. The court has

adopted a timetable that allows for 110 days for public comment and

response. While awaiting approval, the Bell System will continue to press

ahead with the reorganization process.

Although the consent decree allows up to 18 months from

its effective date of Aug. 24, 1982, to complete divestiture, divestiture

has been planned for Jan. 1, 1984, because "the problems of financing in

this time of uncertainty are already acute, and it is critical to the

companies' efficient accounting, auditing and financial reporting that the

divestiture not occur in the middle of a reporting period." The plan allows

for a one-year period following divestiture - a so-called "true-up" time -

during which asset and personnel assignments can be corrected, if necessary.

The Divestiture Process

The first step of the divestiture process is the internal

reorganization of the operating companies. Operating company facilities,

employees and books of accounts for those parts of the business relating to

exchange services and printed directories, which will remain with the

operating companies, will be separated from those parts of the business

associated with the provision of customer premises equipment and

interexchange service, which will become the responsibility of AT&T. Based

on this separation, each operating company will create two wholly owned

subsidiaries. InterLATA facilities, personnel and other assets will be

assigned to an interexchange subsidiary, while customer premises equipment,

related facilities, personnel and other assets will be assigned to a CPE

subsidiary.

Each operating company will then transfer to AT&T, by

means of a dividend, the stock it holds in the newly created subsidiaries.

As a result, the operating companies will no longer own any interexchange or

CPE operations, and AT&T will have separated its exchange holdings from its

interexchange and CPE holdings.

The transfer of these operations will involve a shift of

about 10 to 20 percent of operating company employees.

Assuming approval of the reorganization plan by U.S.

District Court Judge Harold Greene in April or May, all the new companies

will be incorporated in May or June. These new companies include the

interexchange and customer equipment subsidiaries to be established by the

operating companies, the seven regional holding companies with AT&T as the

sole stockholder of each regional company, the Central Organization and the

cellular mobile service company.

On Dec. 31, 1983, actual divestiture will begin. The

operating companies will transfer the interexchange and CPE subsidiaries to

AT&T AT&T will transfer its ownership in operating company exchange,

exchange access and directory operations, as well as the Central

Organization and cellular services subsidiaries, to the seven regional

holding companies on divestiture day.

AT&T will then distribute the common stock in the holding

companies to AT&T share owners.

The outcome of the divestiture process will be the

creation of the seven regional holding companies, each of which will own the

operating companies in its region. The divested companies will provide

exchange telecommunications and local access service within their respective

Local Access and Transport Areas, printed directories and, if they choose,

new customer premises equipment. Each of the regional companies will also

own one-seventh of the Central Organization, as well as the stock of one

regional cellular services company. (For more information about the

Southern/South Central holding company, see the article beginning on page

26.)

The remaining AT&T will consist of eight organizations.

AT&T Corporate Headquarters will continue to be responsible for setting

overall corporate strategy and the allocation of resources among AT&T lines

of business. An interexchange entity will consist of the Long Lines

organization and those operating company operations related to interLATA and

international services, including the necessary operator services. An

embedded base organization will manage equipment on customer premises or in

company inventories that will be assigned to AT&T upon , divestiture. The

other remaining AT&T organizations will be AT&T International, Western

Electric, Bell Laboratories, American Bell Inc., and 195 Broadway Corp.

The "Bell" Name

The plan also proposes guidelines for the use of "Bell"

in corporate names. AT&T and the operating companies will not use any common

corporate name, but each may use "Bell" in their corporate names, so that

the operating companies and their holding companies could use such existing

names as Southern Bell and Illinois Bell, as well as such new names as

Northeastern Bell or Midwestern Bell.

Similarly, AT&T could use such existing names as Bell

System or American Bell, as well as such new names as Bell Intercity or